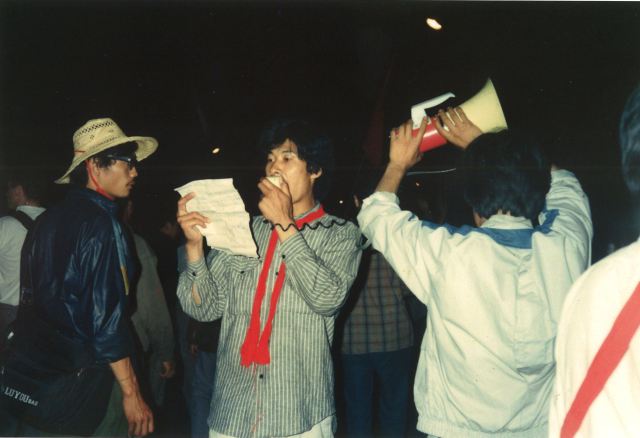

Han Dongfang was 26 years old when he walked outside of his tent on Beijing’s Tiananmen Square on June 3rd, 1989, to see the trails of tracer bullets as the People’s Liberation Army opened fire on his fellow democracy protesters, killing hundreds of them. Twenty five years later in Hong Kong, where he lives in exile, Han worries about the fate of the city’s thousands of young demonstrators making similar demands for reform.

The demonstrators are now in the second week of mass protests over China’s decision to limit direct elections in Hong Kong to candidates approved by a pro-Beijing nominating committee—demonstrations that have drawn comparisons with China’s 1989 democracy movement. Quartz spoke to Han, who was thrown in prison for 22 months for organizing workers, and now runs the labor advocacy non-profit China Labour Bulletin in Hong Kong. Han has been following and attending some of the protests in Hong Kong.

Quartz: Do you think civil disobedience is the best way for people in Hong Kong to push for free elections?

Han Dongfang: There’s not much choice. What really provoked this is that you can only vote based on [Beijing’s] selection. That makes people feel they are stupid. They are screwed. You spit on their face and you don’t expect they will say something? It’s the arrogance of power. You think you have force therefore you become lazy. You become arrogant. You don’t bother to go into the hard work of looking for civilized solutions. You stop thinking because you think you don’t have to.

Q: Do you think the Chinese government is like that right now?

HD: Some of them, yes. I believe so, I am afraid. Especially the people who are in charge of analyzing Hong Kong.

Q: The protesters are running into problems of disunity, exhaustion, attacks by thugs, and anger from local residents. In 1989, how did you deal with this?

HD: Once you enter this kind phase where maintaining this level of excitement becomes one of the goals, that is poisoning. It sounds strange, how can you not maintain high spirit of the movement? But once this becomes the goal, that’s dangerous. In our labor work, we don’t maintain high spirit for the sake of it. Once we have the negotiating opportunity we immediately grab it.

Q: How would you compare the protesters in Hong Kong today to Beijing in 1989?

HD: At that time [in 1989] students came from different universities and each university you had some sort of election and you had leaders. And when you make a decision, people know how the decision is made and [if some] are against it, they can follow the procedure to overturn it, but here you don’t have this. At least from what I can see.

Q: Does that mean you are worried about the protests escalating too far?

HD: Street protests have their own rhythm. No one can plan, no one can completely control and direct it, and as I said before there is no democratic process for people to follow here. You just need a small number of people that can be a trigger point.

Q: Are you worried about the government using force to put down protests?

HD: If people are powerful [and] have weapons—it’s easy for people who have those things to look down on others like you’re nothing, a piece of shit. It’s easy for those people to forget how to be rational. Sometimes these people, at some point, they just can’t wait for the moment that they have the excuse to use force. It’s not only about the communist Chinese government. To my understanding it’s human. The street protesters, when they see this, they are psychologically provoked. And for both sides, the irrational part becomes the winning element.

Q: Do you think the People’s Liberation Army, which already has between 8,000 and 10,000 troops stationed in Hong Kong, could come out to put down the protests?

HD: I don’t believe that. People do learn and sometimes when we talk about those people and we don’t like how they did something many years ago, we tend to emotionally say, “These stupid people, they never learn.” Let’s put some basic faith in humanity.

Twenty five years ago, the PLA ran into a protest. At that time, China was different from today. You don’t compare. Sometimes when you tell people that it’s different, it sounds like you are complimenting the Chinese government. But sometimes you don’t compliment or criticize. There are other things to say.

I do believe the mainstream within the Chinese Communist Party did learn the lesson 25 years ago. And I do believe that most of them don’t want to send the PLA to Hong Kong to deal with this. It’s suicidal. I don’t even believe that if the similar thing happened in China in Beijing again, that they would send PLA tanks again. PLA tanks in Hong Kong streets? I don’t believe so.

Q: Do you think free elections in Hong Kong would inspire similar demands in China?

HD: I wouldn’t go that far. The majority of mainland citizens—let’s not say citizens, we’re not real citizens—the population, are not even dreaming of taking Hong Kong as example to follow. The Chinese government doesn’t need to worry if Hong Kong practices universal suffrage that it will affect the mainland, one city by another, and one province by another.

But look at it another way, mainland China cannot avoid developing into a democratic system. The only difference is which way you want to do it. Gradually, step by step without stop or will you wait for another dramatic historical point like the collapse of the Soviet Union? China will go democratically, no question, but how? At what cost? And that’s the question. It’s not whether China will have it. It’s how to have it. So, if you look at Hong Kong [not] as a threat but rather as a model, as a trial, a pilot, you can practice part of it, how to organize elections, how to start the process, what to avoid, what to introduce.

Q: Will we see protests like these in Hong Kong or those in 1989 again in China soon?

HD: There’s always dissidents. But the majority of the population is not thinking the same way. For example, the workers. Now in China, the biggest protests are from farmers for their land and workers for their salary. Workers are often more organized, and more determined, and if you observe their protest and strikes—it could be several hundred people, several thousand people, even several tens of thousands—none of them demand political change.

Therefore the biggest and most well organized protest is not politically motivated, but it doesn’t mean it has no impact on the political system. Economics, social, and politics are all interconnected. If workers wanted to bargain with employers six, seven, eight years ago, the police would break the strikes, beat them up, arrest and sentence the leaders. Now, the government doesn’t do that. They pressure the employers to bargain with the employees. Do you think this is only economical, if you have already changed the government’s behavior?

Q: What if nothing comes of the protesters’ efforts and they’re left just angry and frustrated?

HD: In 1989, I was young—I was 26. Now, when I see a conflict or difficulties, immediately my mind runs into this logic—iwhere is the solution? There’s no time to feel sad. No time to feel angry. We do feel sad if it’s a sad story and we do feel angry if it’s an angry situation, but as fast as possible we should get out of the anger, get out of the frustration, and start thinking about what should be the solution.

Once you realize there’s no where to land your anger and you keep everything within yourself, it’s you that is being destroyed. Those people you’re angry at, they don’t feel it. They don’t even see you. So you have to find a solution to get out of this. It’s not easy to get out of anger.

Q: Do you have any advice for the demonstrators in Hong Kong?

HD: Not much. The main thing is whether there can be a compromise reached. To make [chief executive] CY Leung lose his position is not the goal. To make the central government lose face is not the goal, to have everything or nothing is not the goal. It’s whether we can make a step forward.

I would say this movement so far has already made an effort, and don’t tell me the central government doesn’t listen, never listens, and hasn’t heard. And I don’t think the Hong Kong people didn’t feel the massive power of this social movement. I think every party has grown further during this movement.

Now we are at another stage. How can we maintain this? How can me make it not who will lose or who will win but rather how to win together? The central government and the Hong Kong government should think this way instead of caring too much about the face. I would urge every side to put down face and just focus on whether the next step of compromise is a good enough improvement.

Q: Do you say this because you think there was room for compromise in 1989?

HD: I never talk about “if” for 1989. I never go there, sorry. What happened, it happened. It has its own rhythm, so we better focus on now and the next. Therefore, I don’t simply compare these two events. It’s different. Beijing is different than Hong Kong. Twenty five years ago, China was different. So the issues that Hong Kong people are facing are different than Beijing in 1989.

Q: What makes you so sure democracy will come to China?

HD: There is already collective bargaining, There is a democracy, in my opinion, in a factory of 5,000 people and 4,000 are on strike and the government pushes the employer to bargain with employees. This is the practice of democracy, although in an undemocratic system. This is democracy in daily life. This is an improvement. It’s one step toward general democracy, and this democracy building process if you make one step toward, no one can push it back, not even half a step backwards.