The global apparel industry’s contraction has led to widespread protests in China and Southeast Asia. In this article, China Labour Bulletin (CLB) illustrates workers’ collective efforts to defend their rights during the 2023 market downturn. CLB argues that international garment brands should be involved in monitoring suppliers’ labour practices across vast production networks. Workers and unions need to utilise new due diligence legislation and tools to coordinate and fight against a global challenge.

The global apparel industry’s contraction has led to widespread protests in China and Southeast Asia

Photo credit: Frame China / Shutterstock.com

- The global apparel industry’s contraction has led to widespread protests in China and Southeast Asia. In this article, China Labour Bulletin (CLB) illustrates workers’ collective efforts to defend their rights during the 2023 market downturn.

- Factory relocations within the region often led to labour rights violations and a variety of reactions based on local contexts. International garment brands should be involved in monitoring suppliers’ labour practices across vast production networks.

- This study of how worker organising and union representation varies in the region shows that workers and unions need to utilise new due diligence legislation and tools to coordinate and fight against a global challenge.

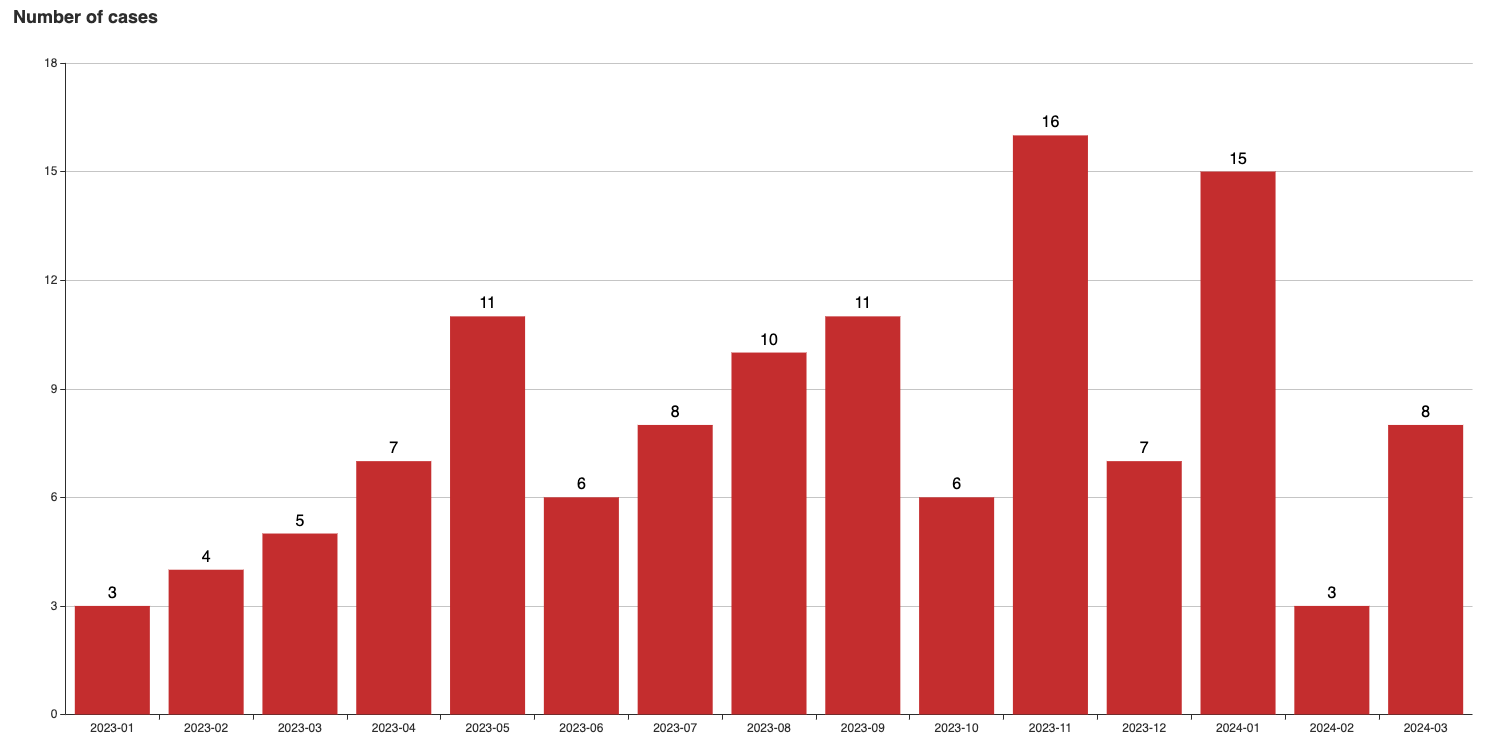

Since last year, collective actions by workers in China’s garment sector have surged in coastal provinces like Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Fujian, where most export-oriented factories are located. The number of garment workers’ protests in CLB’s Strike Map rose from 12 in the first quarter of 2023 to 29 in the fourth quarter. The number of cases in the sector was still high in the first quarter of 2024, with 26 cases recorded.

Graph: Garment workers’ protests in China

Source: CLB Strike Map

Throughout 2023, the Strike Map logged 94 incidents of garment workers’ collective actions, a huge spike compared to only six cases in 2022. Strikes and protests were concentrated in the factories that produced finished products, such as clothing (30 incidents) and footwear (25 incidents). Workers protested against wage arrears and unpaid social insurance, and demanded layoff compensation when factories announced closure.

Strikes related to wage cuts and layoffs also broke out in Southeast Asian countries, where garment suppliers and brands have moved their supply chains into. The most notable protest was led by thousands of garment workers in Bangladesh in late October 2023, in which workers demanded a proper monthly minimum wage increase in Dhaka and the industrial district of Gazipur. The protests, although presented as merely centering on wage increase, erupted amid factories operating at limited capacity or even closing.

In this article, CLB illustrates how the changing business strategy of international fashion brands led to protests in China and more broadly in Southeast Asia, with examples in Bangladesh, Vietnam and Indonesia. It will also show how fashion conglomerates refrained from directly addressing the labour violations in their supply chain, as well as the conflicts between factories and workers. The multinational brands should conduct adequate due diligence to evaluate the impact of their decisions on workers, especially with new binding legislation being enacted and implemented.

Garment conglomerates slashing orders had rippling effects across China and Southeast Asian countries in 2023

International garment brands largely withheld their expansion in 2023. In March 2024, Adidas revealed in their annual report that their revenues in 2023 were basically flat compared to 2022 and they had their first loss in over 30 years. Compared to Adidas, the H&M full year report 2023 shows that the group’s net sales for the financial year experienced an increase of 6 percent. Still, both companies stressed their focus on “cost control,” which means reducing supplies from contractors, being flexible in their orders to respond to customer demands, and closing stores.

After the financial crisis of 2008, the garment industry has gone into another cycle of expansion and competition. The entry of online retailers and new Asian companies operating in the global market have vastly boosted production, while the growth of demand has been unable to keep up with. A journal article studying the crisis in the clothing industry quoted the secretary-general of the International Apparel Federation saying that “there is an enormous mismatch between demand and supply”, resulting in “price pressures caused by an enormous overproduction”. The industry’s overproduction before the global pandemic ran at 30 to 40 percent each season, and more than 20 percent of products (not ever used) ended up in landfill.

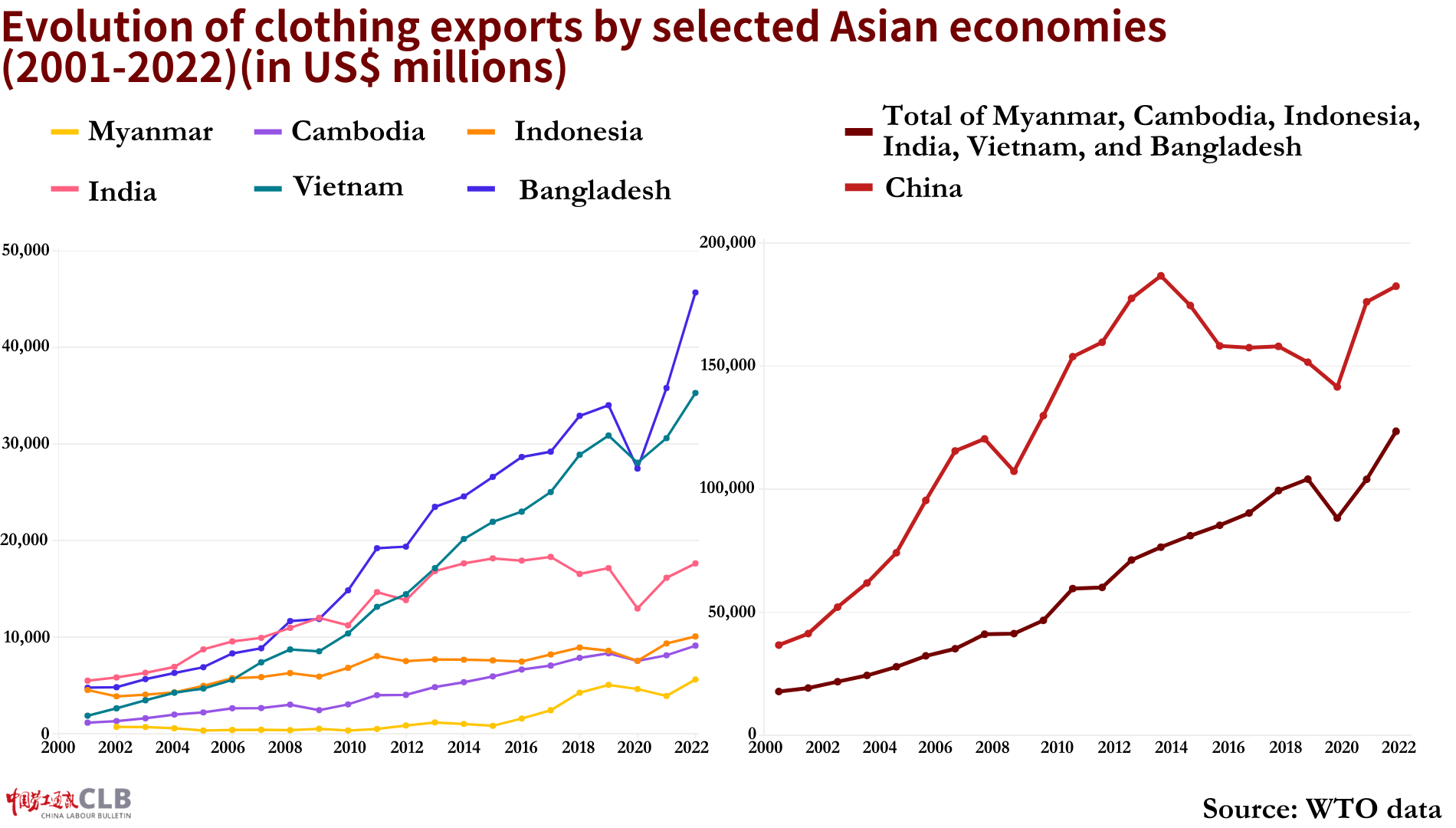

Global fashion brands have been outsourcing their production facilities and rewiring their supply chains for decades. To respond to the new market conditions and stay profitable, companies have shifted their supply chains out of China in search of even cheaper labour. Bangladesh and Vietnam are the two countries that have received the most capital. Cambodia and Myanmar’s export growth rates have also greatly increased, with the latter growing by more than 700 percent since 2019. China remains the world’s top clothing exporter, but its share of global apparel export value has decreased from 37 percent to 32 percent between 2010 and 2022.

The geographical expansion of the garment industry in the past decade means that when international brands decided to cut orders to stay profitable in 2023, the ripple effect impacted many more countries and workers in both China and Southeast Asia.

Garment workers in China protest wage cuts and watered-down compensation as orders were cut

Since last year, CLB has been documenting more strikes and protests related to the export garment industry in China. On 14 April 2023, workers at the Jiaxing Quang Viet Garment Company in Zhejiang province went on strike over wages. The Taiwan-owned factory produces for Adidas, New Balance and other major international brands.

As global brands cut their orders for the factory’s cotton sports clothing and down coats, workers found that their monthly wage of less than 4,000 yuan was significantly lower than what was promised in job advertisements–that workers can make 7,000 to 10,000 yuan per month. Workers demanded that factory representatives should give them a clear explanation for this disparity.

During this incident, an official from the local trade union told CLB that it was the workers who had “misunderstandings” and the company “has explained the situation.” Workers resumed work after four days of strike and received a meagre pay raise of 100 yuan per month.

Another big protest broke out at the Yangzhou Baoyi Shoe Factory in Jiangsu province as over 1,000 workers went on strike from 29 November to 7 December 2023 to demand a concrete calculation of their layoff compensation. A business report on 25 August 2023 revealed that Taiwan’s Pou Chen, the world’s largest shoe supplier and the parent company of the shoe factory, was on course for a 7.7 percent revenue decline for 2023, after its clients like Adidas and Nike slashed orders.

Photo: The strike at Yangzhou Baoyi Shoe Factory in late 2023

Source: Douyin video, archived in CLB Strike Map

Workers said that there was little overtime in 2023, so the base salary used to determine the layoff compensation did not reflect their typical income levels, and the resulting compensation was low. They also protested against the non-payment of social insurance and housing provident funds, which was confirmed by both the company’s notice and government officials whom CLB spoke to.

Local and municipal-level unions, however, either denied that there was a strike, or were unaware that there was one. It was the local human resources and social security bureau of the economic development zone that participated in the negotiations. In the end, the company agreed to adjust the calculation basis and give workers one additional month’s average salary, and workers resumed production.

These two cases show that the corporate de-risking shifted risks and harms on workers in China, as supplier factories reduced pay and even sped up their relocation plans. Workers took the initiative to go on strike, sometimes winning back some part of their owed benefits. China’s official trade unions, meanwhile, were usually not present to represent workers and support their lawful demands.

Workers in Bangladesh demand proper minimum wage increase, but factories shift responsibility to brands and economic situations

The large-scale protest by Bangladesh’s garment workers in late October 2023 demonstrated how suppliers hide behind international brands on the issue of a meagre wage raise. Since the minimum wage for the garment sector is only revised every five years in Bangladesh, the last revision in 2018 did not keep up with rampant inflation. Workers and trade unions have been asking for the minimum wage to be increased to 208 USD.

Photo: Activists of different garment workers’ unions take part in a protest in front of the Minimum Wage Board office demanding rising ahead of a new minimum wage in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on November 7, 2023

Photo credit: Mamunur Rashid / Shutterstock.com

Workers demanded a proper monthly minimum wage increase after the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) proposed an increase to 90 USD per month, and the government Minimum Wage Board’s final figure of 113 USD failed to meet their expectations. After the protests broke out, workers were met with heavy repression. At least four garment workers died, and hundreds of workers were dismissed.

The BGMEA, an industry association, has been shifting the blame to the global economic situation and foreign brands to defend its low proposed wage increase. In March 2023, the BGMEA complained that buyers and brands were placing orders in small amounts instead of bulk quantities, leading to a reduction of factory production. The executive president of another industry representative, the Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BKMEA), was quoted saying that a drop in work orders is one of the reasons that led to factories running at 50 percent capacity in 2023.

By stressing the financial strain faced by factories, the BGMEA maintained that the new wage structure was reasonable. It publicly defended its stance in November 2023, saying that there is a need to perpetuate the comparatively low wage of the Bangladesh workforce to maintain companies’ competitiveness, disregarding the social inequality between factories and workers.

The protest in Bangladesh shows that even though unions and workers were adamant about raising minimum wage, owners of supplier factories were resistant to a pay rise and blamed the purchasing patterns of international brands for low wages. Although this push and pull is between workers and factories, the impact of regional supplier and brand decisions is felt by both groups.

Strikes break out as supplier factories in Southeast Asia pass on burdens to workers

Apart from the large-scale and sustained protests of Bangladesh’s garment workers in November 2023, the reduction of orders and price cuts from international brands have also led to various small-scale protests in various Southeast Asian countries. CLB compiled some notable cases (see map graphic) to show the widespread effects of brands’ decisions on workers’ livelihoods. To highlight a few:

- On 10 February 2024, workers of two ready-made garment factories in Narayanganj, Bangladesh, staged protests as they were officially laid off without receiving the corresponding compensation. One factory is under the Crony Group, which claims to produce for brands such as Tom Tailor, Kroger, Zara, Mango, and more. Another factory is under the Rupashi Group, which has Zara, Inditex, Pull&Bear, Forever 21 listed as its clients.

- On 30 May 2023, garment workers in three locations in Java, Indonesia were facing a massive wave of layoffs. Each of these three garment factories were under negotiations with workers’ unions, as the undisclosed company was having difficulties paying severance pay. A report by the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre said that there was no sign of a recovery in the country’s textile industry.

- On 25 August 2023, hundreds of workers participated in a protest against the layoff plan of South Korean-invested garment firm Nobland Vietnam. The company said that a plunge in orders forced it to restructure by laying off workers. For those that wanted to keep their jobs, the company offered a new productivity-based salary scheme, which pushes workers to increase their output while cutting the annual raise that is based on years of service. The strike prompted the enterprise union to request the company to reconsider employees’ demands.

International fashion brands need to establish better safeguards around disengagement in contracts and supplier codes of conduct, especially when supplier companies have been using various ways to maintain their profitability and deflect cost pressure onto workers. The trends show that workers are laid off without proper severance pay, their calls for higher minimum wages are thwarted by industry and government power, and some had no choice but to accept new wage systems and were pushed to work even harder with a reduced workforce. It is important to observe the stances and responses of brands to the deteriorating labour conditions they indirectly created, which is described in the next section.

Local unions must bring international brands to the bargaining table

In all the garment workers’ protests in China that CLB collected last year, international brands were not seen getting involved in the negotiations between factories and workers. In situations where there were negotiations, as in the cases of Jiaxing Quang Viet Garment Company and Yangzhou Baoyi Shoe Factory, only management of the supplier factories and the local officials are present.

As for the large-scale protest in Bangladesh on minimum wage negotiations, international brands mostly took a reserved position by refusing to express any stance. Companies like Levi Strauss & Co said it has “encouraged the Government of Bangladesh to establish a fair, credible and transparent process for regular minimum wage setting.” Only Patagonia expressed support for a minimum wage of 208 USD per month, the amount that workers asked for. In general, fashion brands refused to acknowledge their influence over pricing pressure. A lecturer of Fashion Policy at Columbia University pointed out that pressure on factories “does start with brands and retailers, and […] it’s just a conversation that the fashion industry keeps trying to resist. But if we want to fix wages, we really have to fix the pricing problem.”

In Indonesia, the effects of garment unions’ negotiations with factories are also largely limited by international brands. The garment union Serikat Pekerja Nasional (SPN) shared with CLB that factories were pushing back on their wage increase demands, claiming that the brands’ order prices were too low. After the brands cut more than 30 percent of their orders to the supplier factories, workers’ wages were in turn lowered by 25 percent. SPN asked the brands’ subsidiaries in Indonesia to provide an explanation, but was refused. On the other hand, factory management turned down their request for details of the orders during wage negotiations.

To bring international brands into the bargaining process and discuss the issues of purchasing prices, CLB has been advocating that unions in China and other countries in the Global South should engage with international brands on issues of pay and benefits, workplace safety, and other labour conditions. In the case of Jiaxing Quang Viet Company, CLB offered to the local union the example of a Dutch intermediate court decision, which went against a Dutch brand for breach of contract for cancelling its orders at the supplier’s factory in Vietnam. After knowing that the court ruled in favour of the supplier as the brand had signed a 2018 contract stating it would not cut its orders for three years, the local union was more interested to know the details of how to engage brands, and discuss ways to support workers when factories face economic difficulty.

International brands need to be brought closer to the bargaining table to remediate harm, as many issues faced by workers in the supply chain originate from at the top. In the final section, CLB would highlight the new tools presented by the emerging corporate human rights due diligence framework that could be useful for the unions during workers’ protests and the collective bargaining process.

Enforcement of corporate due diligence laws brings a new tool for unions in Global South

CLB’s new report illustrates how new developments in corporate due diligence legislation in the EU and European countries can serve to protect workers’ rights. For instance, to provide further support for the collective bargaining process, local unions can now use the new German Act (i.e. Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains) to their advantage if the garment factories were supplying to German companies such as Adidas, Puma and Hugo Boss.

Due diligence tools include provisions for workers and unions to be better protected against retaliation from supplier factories, such as laying off worker representatives or dispelling workers by violence. The German Act requires companies bound by the law to respect the right of all workers to form and join trade unions of their choosing, to bargain collectively and to engage in peaceful assembly (section 2, (2), point 6, a)). It also prohibits the use of private or public security forces to impair the right to to organise and the freedom of association (section 2, (2), point 11). Therefore, if supplier factories aim to break strikes and unions, their German clients have the responsibility to take remedial measures.

It is not uncommon to see supplier garment factories owing wages and social security benefits when orders are cut. The German Act states that these are considered human rights risks and prohibits withholding an adequate living wage–which not only amounts to the minimum wage, but is also determined in accordance with the regulations of the place of employment (section 2, (2), point 8). Unions can now urge German international brands to conduct due diligence investigations on nonpayment of wages, social security and also the refusal of paying layoff compensation in their supplier factories.

Above are just some of the examples of how a new legislation can be used by unions in China and in the Global South in situations where it applies. As more legislations on corporate due diligence are now being discussed and passed in Europe, CLB believes that it is important for unions in the garment sector to engage international brands on issues of wage cuts and layoffs through due diligence procedures and collective bargaining. Meanwhile, international brands should actively take responsibility for their changing purchasing practices, which have caused large-scale labour protests in China and Southeast Asia.

This article is a collaboration between China Labour Bulletin and the SOAS student placement program, with contributions from Andrea Pardo Amil.