CLB examines how Pou Chen’s relocation of production capacities from China led to strikes in southeast Asian countries. It highlights that labour conflicts do not stop after factories are relocated.

- In this article, China Labour Bulletin shows that the global shoe supplier Pou Chen’s profitability is directly related to its relocation strategies in Asia in the past decade.

- The company’s relocating decisions have brought strikes to their factories in southeast Asian countries. For example, workers were continuously and militantly demanding better pay and resisting the company’s wage policy in Vietnam.

- While it would be hard to argue that companies like Pou Chen cannot relocate to other countries, factories should establish a regular mechanism to listen to workers’ voices and improve working conditions.

- In order to better protect labour rights, unions in the Global South need support on collective bargaining to engage international brands in the process.

After the closure of Yangzhou Baoyi, a subsidiary of the Taiwanese shoe company Pou Chen in Jiangsu, China, in December last year, China Labour Bulletin (CLB) covered the incident from the angle of worker organizing as well as investigating the local government and union’s responses.

In this piece, CLB examines how Pou Chen’s relocation of production capacities from China led to strikes in southeast Asian countries. It highlights that labour conflicts do not stop after factories are relocated. Instead, they are transferred to other countries. This article also points out the need to develop collective bargaining in these countries, as companies capitalized on the lack of workers’ organizational power to expand their businesses.

Pou Chen’s cost-cutting strategy: a shift from China to Vietnam and Indonesia

Pou Chen, established in 1969, is a Taiwanese company focusing on production and sale of footwear products. The company claims it is the largest shoe making company in the world, supplying to international brands such as Nike, Adidas, Asics, New Balance, Timberland and Salomon. A magazine said that one out of five shoes is made by Pou Chen.

The company set up factories in Zhuhai, Guangdong early in 1988. Unlike some Taiwanese companies which only focused on mainland China, Pou Chen’s geographic layout included other Southeast Asian countries as early as the 90s, with factories established in Indonesia and Vietnam early in 1992 and 1994 respectively.

Starting in the past decade, Pou Chen has increasingly altered its factories’ distribution. The first trigger point was the global economic crisis in 2008. The reduction of the global footwear market in 2009, coupled with rising wage levels and the newly implemented Labour Contract Law in China, prompted a group of Taiwanese companies to adjust their factory investments amid the economic crisis. A report published by the IBTS Investment Consulting Group (台湾工银证券投顾) in 2010 estimated that the company’s production lines in Vietnam and Indonesia would increase by 8.1% and 8.5% year-over-year respectively, while the increase in China would only be 5.5%.

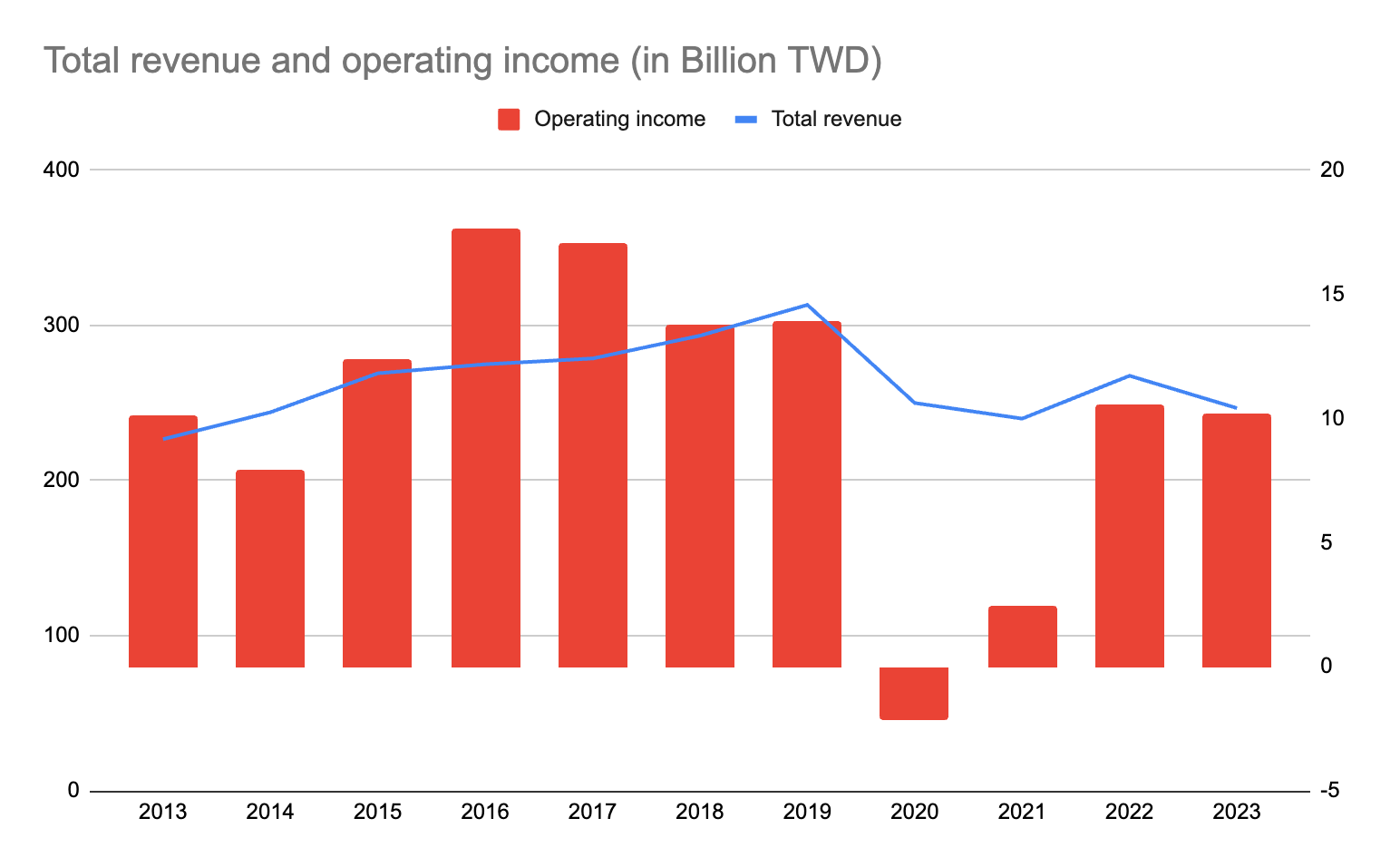

The broad implementation of social insurance contributions after 2011 also translated into a loss of profits for Pou Chen. The annual report of Pou Chen stated that their operating income dropped by more than 20% in 2014. Its net profit margin also went down after 2013, as China’s social insurance requirement and wage level were raised.

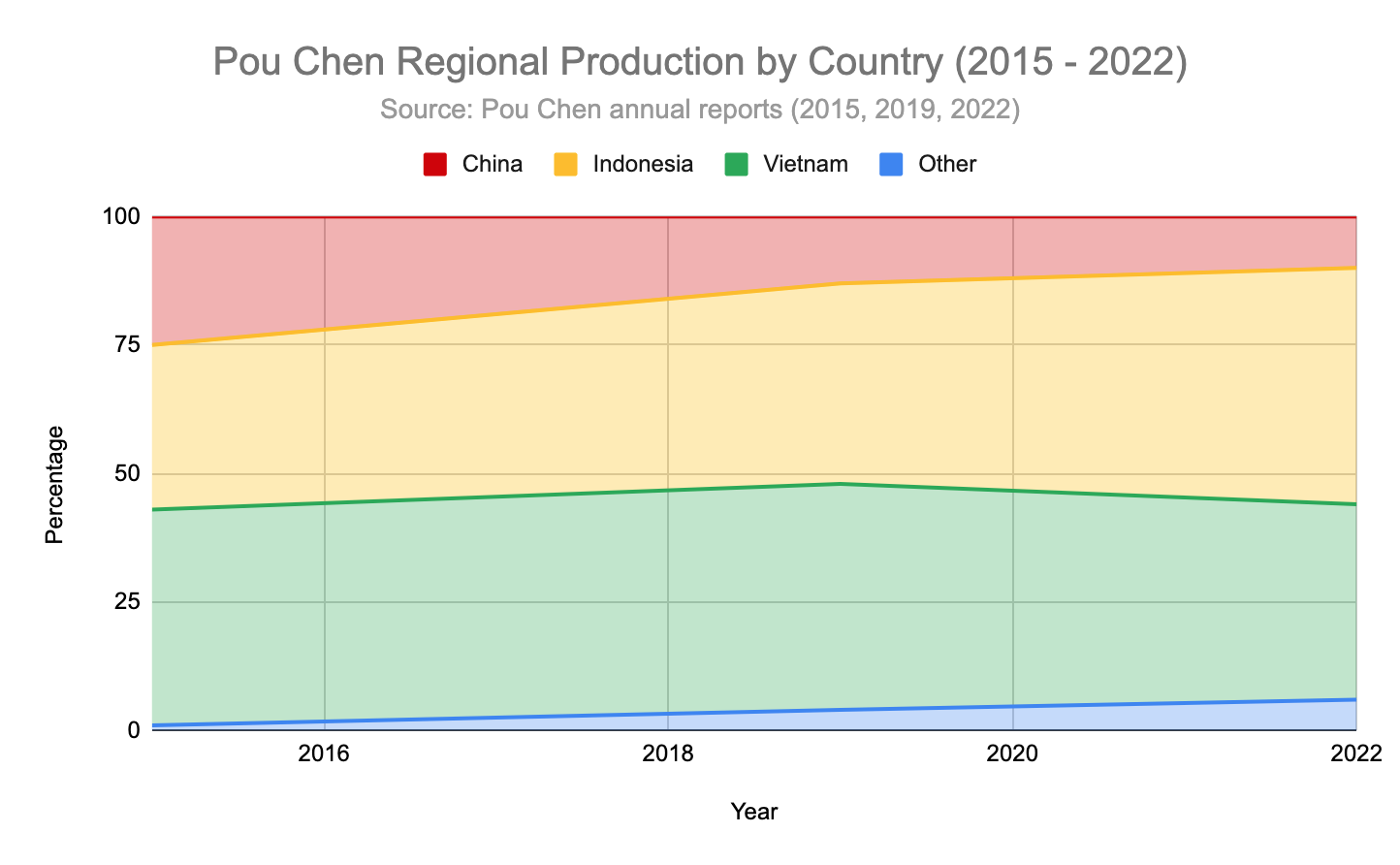

The 2014 Yue Yuen massive layoff was the prelude to Pou Chen’s reaction. Yue Yuan, a subsidiary of Pou Chen, operated an enormous shoe factory in Dongguan, Guangdong. In April 2014, over 40 thousand workers went on strike for two weeks in Yue Yuan, protesting underpayment of pension contributions as well as fearing that the Dongguan factory would be closed (for more details, please refer to our 2022 report, chapter 4, which discusses adequate social security). Vietnam initially emerged as the preferred location to replace mainland China, with its share of shoe production reaching 42% in 2015, while China’s share dropped to 25%.

In 2020, the global pandemic triggered another massive economic contraction. Pou Chen suffered a severe financial loss of 2 Billion TWD in operating income that year. The subsequent economic downturn in the past three years also meant the company was unable to recover their revenue and operating income to pre-pandemic levels.

The reduced revenue, coupled with the strict restriction policy during the pandemic and rising trade tensions between the US and China, pushed Pou Chen to increase its relocation outside China. According to Pou Chen’s annual reports, in 2015, a quarter of Pou Chen’s production was in China. By 2019, only 13 percent was in China, and as of 2022 that has dropped to only 10 percent. Meanwhile, production in Indonesia rose from 32 percent to 46 percent in the same time period. The other approximately 40 percent has been in Vietnam.

Vietnamese workers’ militant strikes for better wages amid Pou Chen’s engagement with official unions

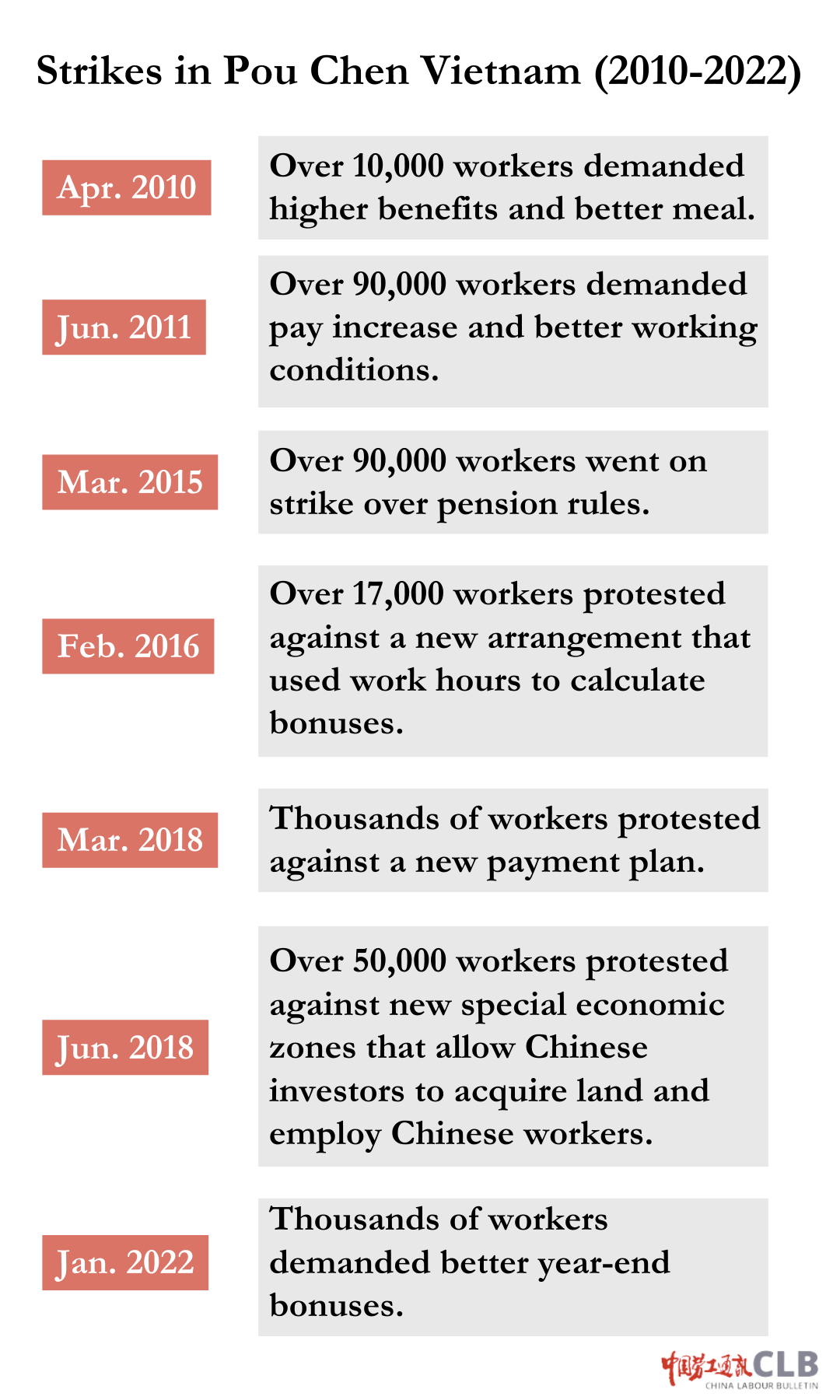

As Pou Chen shifted more production facilities to Vietnam, workers’ protests and strikes started to emerge in the factories. After 2010, at least seven strikes were recorded at Pou Chen’s factories in Vietnam (see table below). Large in scale and occurring from time to time, these strikes were successful in stopping some of the factory management’s policies and led Pou Chen to limit its expansion in the country.

Most of these strikes centered on demanding better pay. In June 2011, more than 93 thousand workers at two of Pou Chen’s factories went on strike, the biggest to date. Workers were dissatisfied with low wage, overtime pay, bonus and poor canteen food. They demanded a monthly wage raise of 500 thousand dong (about 25 USD), but the negotiation broke down after the company only agreed to a raise of 200 thousand dong (about 10 USD).

In 2016, there was again a strike on pay issues. 17,000 employees out of the 21,600 Pou Chen workers in Bien Hoa went on strike for three days in February 2016. Workers were against a new arrangement that used work hours to calculate bonuses, which workers believed would lead to and justify pay cuts. Pou Chen eventually gave in to workers’ demands and canceled the policy, also agreeing to pay workers for the three strike days. A similar case was recorded in March 2018, when the management rolled out a new wage policy. A strike involving thousands of workers, which blocked a highway between Ho Chi Minh City and Dong Nai, forced management to withdraw the policy.

The militant workers at the Pou Chen’s factory in Bien Hoa city staged another strike in 2022 after the global pandemic. Workers complained that the company cut their year-end bonus to the equivalent of between 1 and 1.5 months of salary, from 1.9-2.2 months in the previous years.

Similar to China, independent unions are not allowed in Vietnam, and the only legal union is the state-led Vietnam General Confederation of Labour (VGCL). Various experiments have been made in previous years, including collective bargaining, providing better legal representation for labor disputes, and allowing workers to set up unaffiliated worker representative organizations in enterprises.

Probably because of the rising labor conflicts in Vietnam, Pou Chen was more willing to cooperate with the union. The company announced that they had reached an agreement with the union before announcing a cut in year-end bonus in both 2022 and 2023. Nevertheless, that did not manage to address workers’ grievances completely, as workers still went on strike in 2022.

Pou Chen does not always tolerate the union, though. In Myanmar, Pou Chen suppressed the union by dismissing nearly 30 workers after a 2022 strike that demanded a wage increase.

The need to strengthen collective bargaining in the Global South

As Pou Chen has shifted its production to Indonesia in recent years to leverage its abundant labor force and avoid its conflicts with the Vietnamese workers, the country’s unions feel increased pressure to organize workers for their rights.

The experiences of Chinese and Vietnamese workers have demonstrated that Pou Chen’s subsidiaries act swiftly and decisively to reduce costs in order to enhance profitability. This may involve mass layoffs, the implementation of new wage policies, and the reduction of bonuses.

The initial successes of Vietnamese workers also indicate that cost-cutting measures by suppliers are not merely economic decisions but also political ones that rely on the limited collective power of workers. If workers’ collective voices are not strong enough to engage in negotiations with the company, the company’s decisions are implemented forcefully.

During a visit to Indonesia in 2023, CLB met with SPN (Serikat Pekerja Nasional) and learned about the collective agreement between Pou Chen and the union. While it is positive to see the union engaging in collective bargaining with the company, SPN representatives highlighted significant challenges. International brands are reluctant to participate in the bargaining process and disclose details of their factory orders, effectively hindering wage increases for workers.

To improve working conditions in these regions, unions and NGOs in the Global North should actively support collective bargaining efforts in the Global South. Labor unions within the supply chain should also collectively pressure international brands to participate in wage negotiations and discussions on work-related issues during collective bargaining. Collaborative efforts among stakeholders in the supply chain are essential to globally protect workers’ rights.