CLB conducts a one year, in-depth investigation into the All-China Federation of Trade Union’s reform initiative.

CLB conducts an in-depth investigation into the All-China Federation of Trade Union’s reform initiative

Introduction

The All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) is by far the world’s largest national trade union with an estimated 300 million members and one million full-time officials. The ACFTU is also China’s sole legally mandated union and as such is uniquely placed to help improve the pay and working conditions of a significant proportion of the global workforce. However, the ACFTU has rarely been a staunch advocate for workers, rather it has traditionally seen itself as a servant of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), a so-called “mass organization” dedicated to ensuring harmonious labour relations and smooth economic development for the benefit of everyone.

After four decades of economic reform, however, the majority of China’s workers have yet to really benefit from the country’s so-called “economic miracle,” while on the other hand a small group of Party and business leaders has become obscenely wealthy. Moreover, this extreme wealth inequality has actually worsened over the last five years as China’s fast-paced economy slows down and an ever-increasing number of workers are consigned to low-paid, precarious employment with little or no welfare benefits.

The CCP is acutely aware of the problem as well as the impact it has on its own political legitimacy. Indeed, the Party now seems to have accepted that economic growth in and of itself is no longer the answer and that it needs to focus much more on wealth distribution if it is to retain the trust and support of the working class. The CCP has devoted vast resources to eradicating absolute poverty in China’s poorest rural regions but in order to reduce relative poverty in urban areas and achieve its goal of creating a “moderately prosperous society” in time for its one-hundredth anniversary in 2021, the Party needs the ACFTU to contribute as well.

Starting in 2013, China’s paramount leader Xi Jinping has on numerous occasions called on the ACFTU to do a better job in helping low-paid workers achieve their “China dream.” And in November 2015, Xi Jinping formally launched the CCP’s trade union reform initiative, which was designed to shake up the organization and improve the way union officials carry out their work. Specifically, the reform initiative had two main objectives: 1. “eliminating four impediments” to the ACFTU’s work – regimentation, bureaucratisation, elitism and frivolousness, and 2. “increasing three positive attributes” of the organization – political consciousness, progressiveness, and popular legitimacy. In essence, what these jargonistic terms meant was that the ACFTU should abandon its old bureaucratic ways and focus on concrete measures that could both help workers and restore its own reputation.

The ACFTU has claimed, in an endless stream of statements and speeches, that it has heard the call from the Party leadership. However, it is clear that China’s workers are still far from satisfied with their current pay and conditions. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, well over a million complaints by individual workers were handled by China’s labour mediation and arbitration organizations in 2018. Local labour dispute arbitration committees took on a record 884,223 cases in 2018 with another 214,288 cases handled by external mediators. In the same year, China Labour Bulletin recorded 1,701 strikes and collective worker protests on our Strike Map, and another 1,386 incidents in 2019. These incidents, which occur in every region and cover a wide range of industries, probably only account for around ten percent of the actual number of collective worker protests in China.

In the summer of 2018, CLB decided to use the collective worker protests recorded on our Strike Map as part of an investigation into how local trade union federations in different parts of the country had responded to labour conflict and to what extent they had met the Party’s expectations in terms of trade union reform. Each month, we focused on one particular province, starting with the southern economic powerhouse of Guangdong, followed by Jiangsu, Anhui, Sichuan, Hubei, Guangxi, Shandong, Fujian, Zhejiang, Gansu, Qinghai and Ningxia. See screen shot of CLB’s Strike Map below.

CLB staff selected several of the collective labour disputes that had occurred in each province that month and telephoned the local trade union officials who should, in theory, be responsible for the interests of the workers involved in those disputes. It was not always possible to locate trade union officials at the grassroots level, such as enterprise unions or sub-district unions, but we had more success in talking to officials from district and municipal trade union federations.

Initially, we would ask the officials whether or not they were aware of the incident and, if so, what had been their response to it; had they intervened to help the workers defend their rights, mediated in the dispute or sought to negotiate with the employer to resolve it, or had they simply ignored the workers’ plight? The discussion could then broaden out to a critique of the union’s performance and the difficulties officials had in organizing workers, resolving labour disputes and implementing the trade union reform agenda.

By talking directly to trade union officials on the ground, we could bypass the ACFTU’s well-established propaganda machine and gain a more accurate picture of how the union operates on a day-to-day basis. While some officials were suspicious and reluctant to talk, many were open to our inquiries and talked candidly about their own roles, the frustrations they experienced at work and their hopes for improving the lives of workers.

We analysed the interviews to determine to what extent each local trade union had met the CCP’s stated goals of “eliminating four impediments” and “increasing three attributes.” Each individual case analysis was then combined in an overall monthly report which assessed the performance of the union in the province as a whole. The results, including all interview transcripts, were then posted in a dedicated section of the CLB Chinese website, and sent directly to the trade union federations concerned by post and email.

In total, from August 2018 to June 2019, we conducted about 250 telephone interviews with 95 local trade unions, based on 71 collective worker protests in 12 provinces. Details of all 71 collective protests can be found on our online database.

This research formed the basis of a comprehensive year-end report 中华全国总工会改革观察报告, which was published in December 2019. The report comprises three sections; the first looks at the origins and objectives of the trade union reform initiative (discussed briefly above), the second lays out the findings of CLB’s investigation, and the third part lists our recommendations for what the AFCTU should be doing in order to carry out genuine reform and transform itself into an effective trade union that actually serves the interests of China’s workers.

Main findings of the report

Local trade unions have made new efforts to help workers defend their rights. Since the advent of the reform initiative in 2015, many local trade unions have devoted more financial and human resources towards providing workers with legal advice and helping them defend their rights in disputes with their employer. Most district and county-level trade union federations have now set up worker service centres and rights protection hotlines, and are responding more positively to workers requests for help. For example, all the staff at the Liyang Municipal Federation of Trade Unions in Jiangsu responded enthusiatically to our inquiries about a factory protest over wage arrears that occurred in the city on 15 September 2018. One official told us:

The local trade union represents the interests of workers. People involved in a mass incident like this will not necessarily trust the local government because government officials may deliberately delay or deflect the problem. The workers will then ask for the union’s help but they cannot trust the enterprise union either, so in the end it is the local union federation that is the only one actually representing workers… The identity and role of the trade union cannot be denied.

Enterpise unions are established primarily to meet quotas and do little to actually help workers. The ACFTU has acknowledged that employment conditions in China are changing and that there is a need to focus more on workers in the service and transport sector rather than the traditional manufacturing sector, which is now in decline. In April 2018, as part of the reform initiative, the ACFTU launched a new campaign designed to bring more transport and service workers into the union, concentrating on eight major groups: truck drivers, couriers, nursing staff, domestic staff, security guards, online food delivery workers, sales and real estate agents. In the following months, local unions proudly publicised how they had worked hard to bring the eight groups into the fold; however, they still followed the traditional quantitative model of setting up enterprise trade unions based on quotas established by higher-level unions rather than on the actual needs of workers on the ground. Moreover, many local unions were constrained or frustrated in their efforts to recruit workers by the union’s bureaucratic structure and rigid requirements. For example, one union official in the coastal city of Weihai in Shandong told us:

One day some delivery workers came to the union office and asked about setting up a sectoral union or an enterprise union in the delivery industry. We passed the inquiry to the responsible department. In the end, it was decided that the enterprise these workers were employed in was not part of the ‘Eight Groups’ that the ACFTU had specified, so we could not solve the issue for these workers. Of course, because they are doing logistics and express delivery, they are technically part of the transportation sector. However, our department did not count these particular workers as qualified.

In the nearby city of Qingdao, officials said that unions could only be established by enterprise managers, not by the workers, and that enterprises should only establish one union branch, located in the district they were headquartered in. This meant that workers in other districts had to travel all the way across town to meet with union representatives. This was a completely unnecessary stipulation that made it much more difficult to organize couriers across one municipality let alone the whole province or region where the delivery companies operated.

In the construction industry, which is plagued by wage arrears and an appalling safety record, trade union officials still focus on setting enterprise unions or temporary project unions that do little to improve pay and conditions for workers or reduce labour unrest. Even when agreements are reached to improve wages, the results are often of little real benefit and do not address the workers’ main concerns. A veteran union official in Wuhan, who had been praised by the Workers’ Daily in 2016 for establishing a sectoral wage negotiation system in the city’s construction industry, told us that construction workers could easily earn 300 yuan a day and so pay levels were not the problem. Based on his own experience visiting construction sites, the official said “wage arrears, work safety, and getting ill without medical insurance” were the main problems in the industry that workers wanted to resolve.

Most trade unions still have little understanding of what collective bargaining actually entails. Collective bargaining should be the fundamental aim and core activity of any trade union. However, most trade union officials in China still think collective bargaining is an administrative exercise that involves nothing more than establishing minimum wage guidelines. These wage negotiations are conducted between enterprise or industry federation representatives and local trade union officials and specifically exclude the workers. Most so-called collective agreements are little more than reprints from clauses of the Labour Law and Labour Contract Law and bear little or no relation to the most pressing concerns or grievances of the workers. As a result, workers usually have no option but to take collective action when they want to resolve those grievances.

Local unions are still too focused on non-core activities. Local trade unions across the whole of China engage in a wide variety of side-line activities that take up a huge amount of time and divert resources away from what should be the union’s core mission: organizing and collective bargaining. These side-line activities include poverty alleviation, educational and training programs, helping with employment searches, even marriage introductions, and celebrating great craftsmen and model workers etc.

Poverty alleviation is a particularly burdensome issue for local trade unions because of Xi Jinping’s insistence that absolute poverty must be eradicated by 2020, even if that task distracts from the union’s primary role. When we contacted Director Liu of the Pingchang County Construction Industry Union in rural Sichuan to discuss construction worker wage arrears in his district, he was out of the office working on a poverty alleviation project in the countryside and took our call on his mobile phone. Director Liu readily engaged in our discussion on wage arrears but noted:

I think your suggestions are very good but we have a heavy burden with poverty alleviation right now. All officials in the western rural areas have to participate in it, not just trade union officials, but all government officials now.

Even the new worker service centres set up by many local unions are in essence still side-line projects that detract from the union’s core mission. These centres can provide workers with valuable legal assistance in their fight against their employer but such services are also available at other local government departments, and as such the trade union service centres can be seen as a duplication of resources.

Trade union officials still see themselves as agents of CCP propaganda. This is a deeply ingrained institutional problem in the ACFTU. Trade unions at all levels, just like their local government counterparts, feel compelled to serve the Party by disseminating information about the CCP programs and objectives. However, at the same time, local unions have largely failed to actually implement programs that improve workers’ pay and conditions. In other words, by attempting to serve the Party through speeches and public relations exercises, the ACFTU has neglected to serve the people who should be the ones benefiting from the Party’s policies.

Given the less than satisfactory findings outlined above, the report argued that there was an urgent need to re-orientate the trade union reform program so that in the future it focused primarily on creating an effective collective bargaining system that can bring about a fairer distribution of wealth for China’s workers.

Specific recommendations

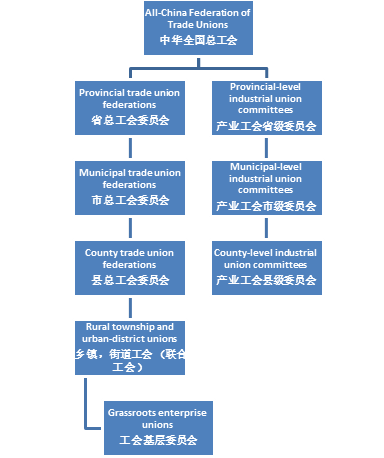

Reorganise the ACFTU with sectoral trade unions at its core. The ACFTU’s current organizational structure basically reflects the hierarchy established by the CCP and Chinese government. See simplified organizational chart below.

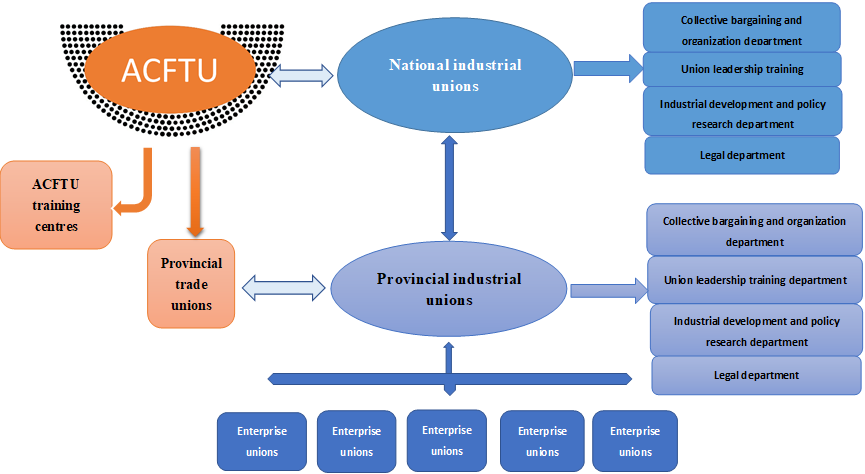

For the ACFTU to operate as a real trade union, and not just an adjunct of government, it needs to undergo a major restructuring process that will place industrial/sectoral trade unions at the centre of its work. These sectoral trade unions should reflect actual employment conditions and focus on grassroots organizing and enterprise collective bargaining. This will eventually establish the foundation for regional collective bargaining across various sectors.

Once an effective regional collective bargaining framework has been established, the current municipal, county and district trade union federations can be phased out and their staff reassigned to the sectoral unions most suited to their skills and experience. However, it may be necessary to retain some sub-district and industrial zone union federations to assist in organizing work at the grassroots. Once restructured, the ACFTU would look more like the more horizontal and integrated organization chart below.

Develop effective collective bargaining strategies for each industry. The report called for the creation of new organizing and bargaining roles for specific industrial unions, and suggested possible approaches that unions in the construction industry and those representing different transport workers could adopt.

In the construction industry, the report recommended that each province create a database of all employed construction workers, and those seeking employment, that includes their professional qualifications, pay-scales, social insurance history etc. This database would help union officials to better understand their members’ needs and negotiate more meaningful collective agreements that include pay, working hours, social insurance, and work safety – in other words, all the issues that construction workers are really concerned about. The union should also provide skills training for its members and use the database to match specific workers to appropriate construction projects in their region. The union would be directly financed by monthly or yearly dues paid by its members rather than relying on contributions from enterprises, as is currently the case.

In the transport sector, there should be specific organizing and bargaining strategies for truck drivers, couriers, and food delivery workers who are employed by different online platforms. For truck drivers, who are primarily independent contractors, provincial unions should negotiate acceptable haulage rates and working hours with the online platforms, as well as comprehensive insurance rates with the insurance companies for its members. Food delivery trade unions, on the other hand, would focus on negotiating acceptable delivery rates and time frames that will enable drivers to earn a decent wage without having to work 12 hours a day or risk their lives trying to make a delivery on time.

Establish a clear union identity and role. Local and enterprise trade union officials need to reposition themselves as representatives of and advocates for workers, and completely discard their current role as propagandists for the CCP. In enterprise unions, trade union officials must be part of, and elected by, the workforce so that the union can be wrested away from the current grip of the employer and management. In this way, union officials will be better placed to bargain over pay, benefits and working conditions. Here, the report addresses the Party directly by stressing that local and enterprise union officials should be imbued with socialist values so as to effectively combat the corporate greed and lawlessness that currently pervades the private sector in China. More than 80 percent of strikes and worker protests in China occur in domestically-owned private businesses, according to data from CLB’s Strike Map, and nearly all are related to violations of labour law by the employer.

Establish a uniform and comprehensive online presence. Finally, the report makes a very concrete recommendation that the ACFTU should establish a comprehensive online presence in one general website that lists all the contact information for all regional and sectoral trade unions across the country, as well as the names and profiles of the relevant officials. This would enable workers and union members to quickly identify and contact the trade union most suitable for their needs and most likely to resolve their grievances. Currently, each local union has its own (usually poorly maintained) website or Weibo/Wechat account which appears to be completely disconnected from other unions.

Future developments

More than four years after the trade union reform initiative was formally launched by Xi Jinping in November 2015, it is clear that the ACFTU’s efforts have been little more than window dressing. It has failed to help realise the Party’s goal of achieving a more equitable distribution of income and workers are still left with no option but to stage strikes and protests in order to resolve their grievances. Like many trade unions around the world, the ACFTU is struggling to come to terms with rapidly changing patterns of employment and the emergence of the gig economy. However, the ACFTU’s difficulties have been exacerbated by its overly bureaucratic structure, its innate inertia, and its reluctance to get its hands dirty and actually organize workers.

In order to jolt the ACFTU into action, CLB will send bound copies of our report to more than one hundred trade union offices in China in the hope that the officials there will sit up and take notice and perhaps begin to discuss their own failings and think about ways to improve their performance. It is possible that some officials will simply throw the report into the trash but if it provokes positive change in just a small part of the union it will have been a success. Trade union reform is a long-term process and progress can only be made step by step.

In the meantime, we will continue our investigation into the trade union reform initiative, calling local trade union officials to discuss their response to strikes and worker protests in their district. This year however, we will base our investigations not on particular provinces and regions but on specific industrial sectors, starting with the construction industry and online platforms employing workers in food delivery, logistics, trucking etc.

The creation of sectoral trade unions is one of the most urgent needs identified by the report and it is also an area where international trade unions can share their expertise and experience. We would encourage international unions involved in the construction sector, transport and services (particularly the gig economy) to reach out to their counterparts in the ACFTU and discuss the issues raised in CLB’s report and hopefully establish a dialogue on the way forward for the trade union movement not just in China but globally.

Researchers who want more details on the trade union reform initiative or the individual cases discussed in the report, please refer to the Chinese original and the trade union reform section of our Chinese website. For an overview of the most recent trends in worker activism, please see our report on the state of labour relations in China in 2019.

We have also produced a quick one-page summary of CLB’s trade union reform project which can be

downloaded here. And

click here for a PDF version of this article.