Strikes by transport workers have long been a feature of daily life in China’s cities but in the last five years there has been a noticeable shift in the nature of these protests, driven primarily by the rapid growth of app-based transport services and the decline of traditional services.

Strikes and collective protests by transport workers have long been a feature of daily life in China’s cities but in the last five years there has been a noticeable shift in the nature of these protests, driven primarily by the rapid growth of app-based transport services and the decline of traditional services such as taxis.

China Labour Bulletin’s Strike Map has recorded nearly 1,400 transport worker protests in the five years between 2014 and 2019, accounting for about 15 percent of the total – see map below. From this dataset, we can clearly see the changes in the industries involved, the geographic location and the number of participants in each protest.

A proper understanding of these trends and the underlying issues giving rise to transport strikes is vital not only for China’s government but also for the official trade union, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), which claims it has now made recruitment and better protection of transport workers a major priority.

Taxi drivers were for many years at the core of transport worker protests in China, with some major strikes involving thousands of drivers and lasting several days. Probably the most famous strike occurred in the southwestern metropolis of Chongqing in 2008 when the then Municipal Party Secretary Bo Xilai personally met with taxi driver representatives to end a dispute that had crippled the city. In the Chongqing strike, as in just about every other dispute, driver grievances centred on the widely-used contract system (承包制), under which drivers paid a sizable deposit and monthly leasing fees (份儿钱) for the use of the vehicle to the taxi companies. The cab companies could arbitrarily raise the monthly fee, while the driver had to cover the costs of fuel, maintenance and repairs. When fees were raised or costs went up, drivers with no other channels to express their grievances would stage strikes in protest.

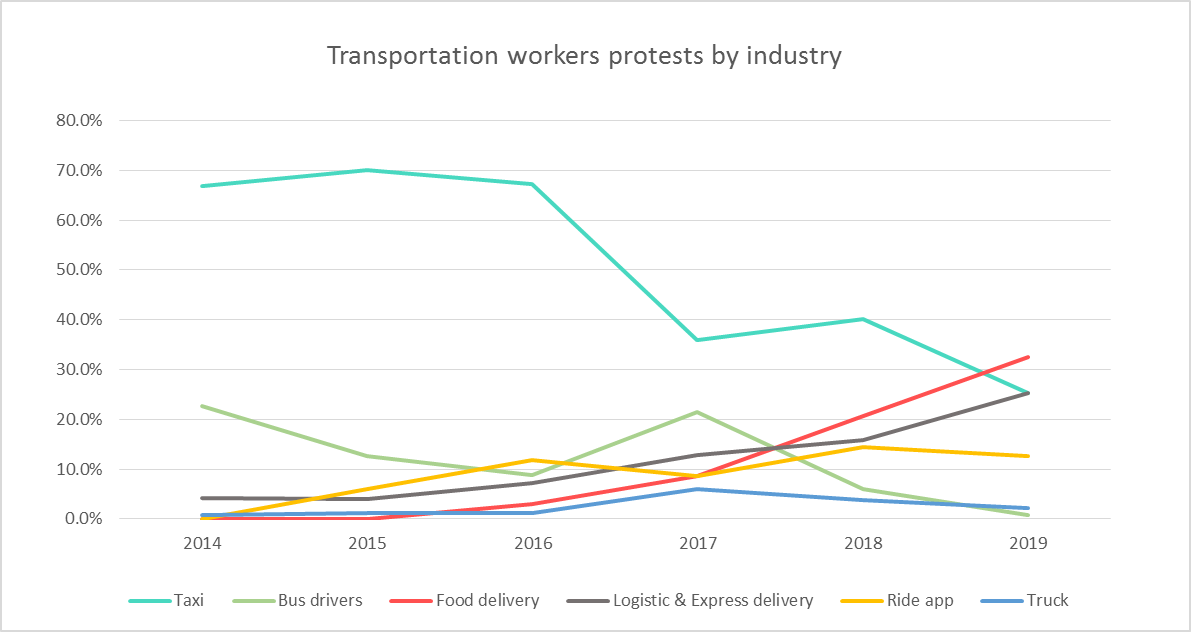

Taxi drivers had also long complained about competition from unlicensed “black” cabs but this complaint became even louder with the entry into the market of ride-app vehicles in the mid-2010s. Striking taxi drivers regularly went on “fishing expeditions” to catch and threaten illegally operating drivers. However, as ride-app drivers became more regulated and started to dominate the market, protests by taxi drivers began to decline from a peak of about 70 percent in 2015 to just 25 percent of the total so far this year.

The focus of many taxi driver protests nowadays is on claiming their operating rights and car ownership from the cab companies. In April 2019, for example, hundreds of taxi drivers went on strike in Nanxian, Hunan, when the management company forced them to upgrade their cars. Drivers were furious at having to pay 160,000 yuan to the company for a new car that retailed at 100,000 yuan, and demanded ownership rights following the upgrade.

Like in the taxi industry, the number of protests by bus drivers and crews has also been decreasing to the point where there was only one bus driver protest recorded this year. Bus company workers, similar to taxi drivers, had for many years been protesting high fuel prices, competition from unlicensed operators and incompetent local government regulators. In 2013, for example, around 100 drivers and conductors went out on strike in Guangdong, protesting low pay and excessive working hours with no overtime. Bus company employees also demanded the end of fines and arbitrary charges levied by management for everything from using too much fuel to replacing tyres. Since 2017 however, bus worker protests have focused more on defensive actions related to wage arrears and compensation following company closures and the cancellation of bus routes by local government regulators. It is possible that the lower number of strikes this year is a sign that the industry is now better regulated but it could also be due to a lack of coverage of protests on social media.

While taxi and bus driver protests were declining, there was a commensurate rise in the number of protests by food delivery and express delivery workers. There were no protests by food delivery drivers at all until 2016 but today they account for 33 percent of all transport worker protests, surpassing the proportion of taxi driver strikes by eight percentage points. One of the most common causes of strikes is a sudden and arbitrary pay cut imposed by the two main food delivery companies, Meituan and Ele.me, who are in a fierce battle for market dominance. With their income reduced, drivers are forced to work even longer hours and more intensely in order to cover their losses. As a result, traffic accidents are commonplace, as shown by CLB’s Work Accident Map, which has recorded 121 accidents, with 19 deaths since the beginning of 2018.

The express delivery sector is likewise highly competitive, with many companies failing or being forced to restructure after over-aggressive expansion plans failed to secure the market share expected. This often leaves drivers out of a job or facing severe losses. The bankruptcy of OTP express in October, for example, resulted in some drivers’ monthly salaries plunging from around 8,000 yuan to just 2,500 yuan a month. So far this year, protests by express delivery drivers have accounted for 25 percent of the total.

Strikes and protests by ride-app drivers have also become a common occurrence in the last few years and currently account for about 15 percent of all transport sector cases. Market saturation has led to drivers’ orders falling to the point where they can no longer make a living. Malpractice is rife in the industry with drivers feeling cheated not only the ride-app companies but by car lease companies that promise drivers an operating permit in return for substantial administrative fees but then fail to deliver on that promise.

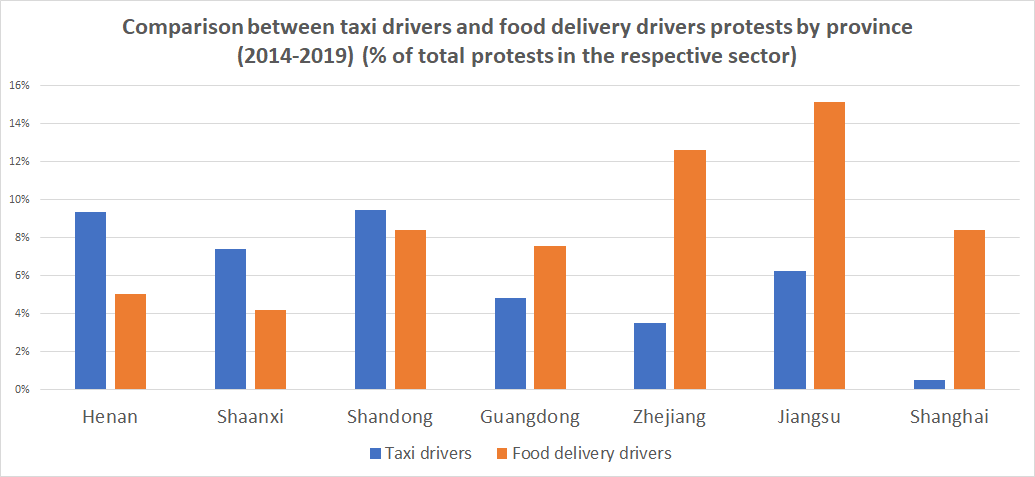

There is a noticeably different geographic pattern for protests by traditional transport workers like taxi and bus drivers and those by new industry workers like food delivery drivers. In the five years from 2014 to 2019, taxi driver protests were concentrated in less developed cities in provinces like Shandong, Henan, Shaanxi and Hunan. Many smaller cities in these provinces have been slow to adapt to the changing nature of the transport sector and taxi companies with influential ties to local governments can still maintain their monopolistic practices that exploit drivers.

Food delivery driver protests on the other hand are mostly found in more developed eastern cities in Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shandong and especially Shanghai. Many office workers in these cities do not have time to leave their desks during work hours and have no option but to order takeout and this has created a huge demand for food delivery services. It has also put tremendous pressure on food delivery drivers to work harder and for longer hours.

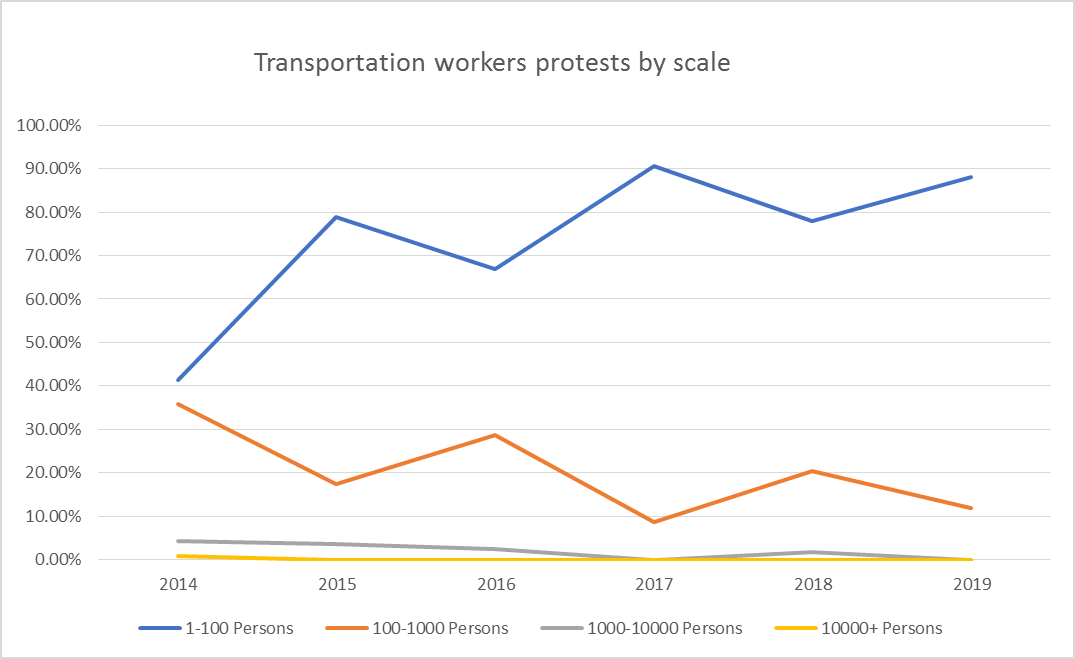

In terms of protest scale, there has also been a clear drop-off in the number of participants in individual transport strikes over the last five years. Five years ago, it was not unusual to see mass protests by thousands of taxi drivers. Today however, the industry is much more fragmented and informal. As such, protests tend to be more localised and short-lived, generally involving less than 100 people. See graph below showing the increase in the proportion of small-scale protests.

The one noticeable exception to this trend of smaller-scale protests is the trucking industry which employs around 30 million drivers across the country. Drivers staged regular mass protests in the mid-2010s and also organized a nationwide strike as late as June 2018. In this most recent protest, the truck drivers demanded higher haulage rates from the app-based companies that now dominate the market to compensate for higher fuel and maintenance costs as well as arbitrary fines imposed by local traffic police.

Through the last five years of transport worker protests in China, the trade union has been conspicuous by its absence. Transport workers have in fact been asking for union representation since the mid-2000s but local union officials have been either incapable or unwilling to recruit them. Many requests to set up taxi driver unions for example were rejected by local officials because they said the drivers were contractors and not technically employees of the cab company.

There were some attempts in the 2010s to reform the taxi industry and create an enterprise system where drivers were formal employees and therefore could form a union. But in most cases local union officials still only negotiated with company managers rather than the drivers themselves when trying to set up a union. The only really successful taxi trade union that CLB is aware of was set up in 2008 in the suburban district of Changqing in Jinan, the provincial capital of Shandong. The union was democratically elected by the drivers and engaged in regular negotiations with the district transport authorities that successfully avoided strike action for many years. However, it seems this model was not widely replicated in other cities.

The trade union missed a golden opportunity to unionise taxi drivers in the 2000s and 2010s. It is imperative now that it does not make the same mistake in the 2020s and fail to organise China’s rapidly growing and essential labour force of food delivery workers, express delivery workers and ride-app drivers. The ACFTU has recognised the need to do a better job in organizing transport workers and ensuring that their rights are protected. Whether or not it has the ability or the political will to do so however is an open question.