More than 95 percent of China’s population are covered by a state medical insurance plan. However, only a small proportion have access to high quality healthcare.

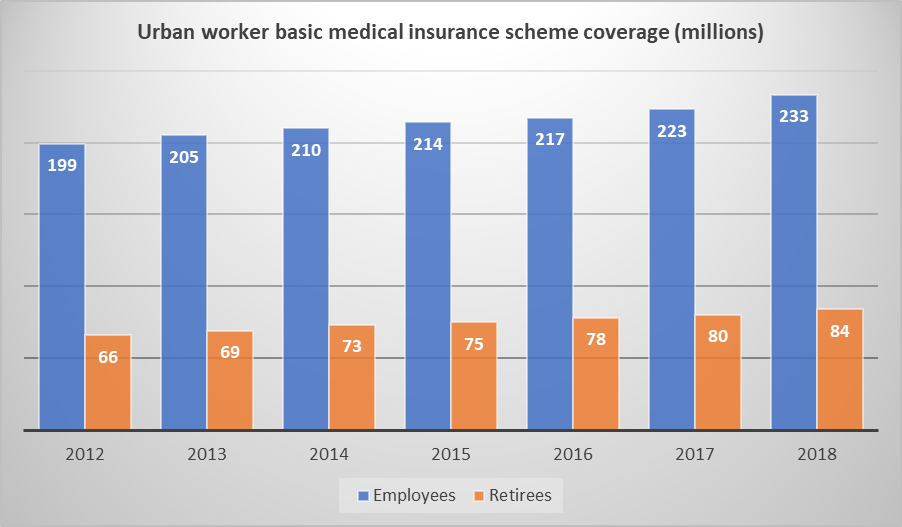

Around ten million workers joined China’s main state-backed medical insurance scheme last year, an increase of 4.6 percent over 2017, according to official figures. That is the good news. The not so good news is that the 233 million employees covered only account for less than a third of China’s total workforce. There are, in addition, 84 million retirees currently covered by the scheme.

The vast majority of Chinese citizens with medical insurance (897 million out of 1.34 billion) are covered by the government-backed urban and rural resident medical insurance scheme, which last year paid out just 627.7 billion yuan or only around 700 yuan per person on average, barely enough to get in the door of a major hospital. The main urban worker basic medical insurance fund on the other hand paid out a total of 1.07 trillion yuan last year, or about 3,380 yuan per person on average for the 317 million people covered.

Data released by the National Healthcare Security Administration shows that the average expenditure for those covered the urban worker scheme who spent time in hospital last year was 11,181 yuan. By comparison, the average hospital expenditure for those covered by urban and rural resident scheme was just 6,577 yuan in 2018.

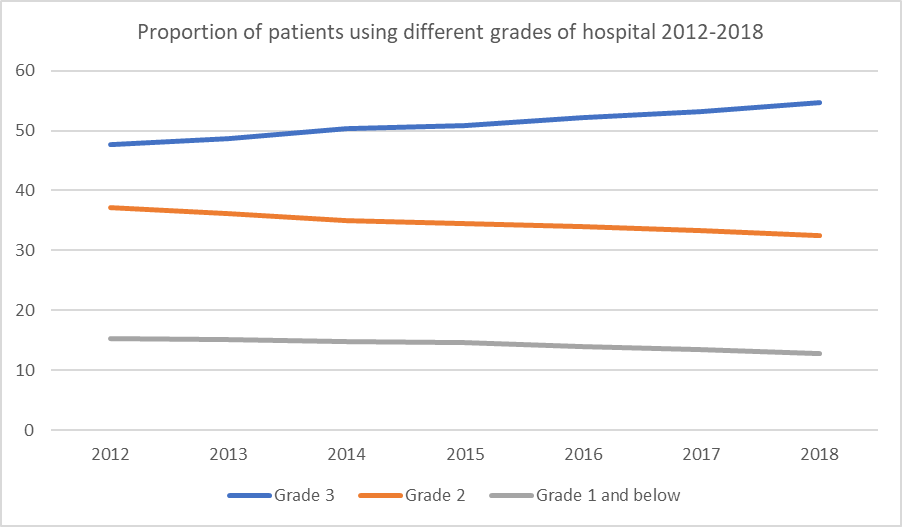

The majority (54.7 percent) of patients covered by the urban worker scheme stayed in large specialist (Grade 3) hospitals in big cities, 32.5 percent in mid-level (Grade 2) hospitals and only 12.8 percent in (Grade 1) grassroots facilities.

There has been a steady increase over the last few years in the percentage of patients covered by the urban worker scheme using top-of-the-line Grade 3 facilities. While this has benefited those workers and retirees lucky enough to be covered by the scheme, as noted in our most recent newsletter, this trend has also placed a huge strain on China’s overburdened top-tier hospitals and left the lower grade hospitals that desperately need the money from patient fees under-utilised.

It is mainly patients who are covered by the less favourable urban and rural resident scheme who use lower tier hospitals. One important factor to note here is that the proportion of expenses covered by the urban and rural resident scheme decreases dramatically the higher up the hospital care quality ladder patients go, with less than half of the fees covered in many Grade 3 hospitals, making them basically out of reach for low income earners.

China’s 288 million rural migrant workers and their families are among those with the least access to decent healthcare. Even though all urban enterprise employees are supposed to have medical insurance as part of their conditions of employment, only 22 percent of migrant workers were covered by the urban worker basic medical insurance scheme at the end of 2017. It is particularly difficult for migrant children to get health insurance and, in most cases, parents end up paying the majority of medical expenses out of pocket. The exorbitant cost of healthcare means that many migrant workers only visit hospitals in dire emergencies, when it is often too late.