While thousands of Marriot employees in cities across the United States made international headlines with their just-concluded strike over low pay and hazardous working conditions, China’s hotel and catering workers have also been staging widespread strikes and protests but with no union support.

While thousands of Marriot employees in cities across the United States made international headlines with their just-concluded strike over low pay and hazardous working conditions, China’s hotel and catering workers have also been staging strikes and protests, albeit on a smaller scale and scattered across the whole country.

So far this year, CLB’s Strike Map has recorded more than 50 collective protests by hotel and restaurant workers, bringing the total number of incidents over the last five years to nearly 300. Unlike the Marriot strike, the vast majority of these protests in China were uncoordinated and isolated events involving less than 100 employees that would have been ignored entirely had the workers not posted their stories on social media.

Hotel employees in Ningbo on strike on 28 November 2018

Hotel and catering workers are some of the lowest-paid workers in China, they have few benefits, work long hours, often under intense pressure, and have little job security. And yet, these workers will usually only take collective action when they are pushed to the very limit. Nearly all the hotel and catering worker protests recorded on the Strike Map are caused by sudden business closures that leave employees out of work and owed several months wages in arrears. Under these circumstances, workers have no option but to stage protests in the hope that the local authorities will intervene and help them recover their wages.

The local trade union may get involved at this stage as well but is nearly always absent when workers actually need it to help them gain better pay and working conditions.

In 2011, the municipal trade union in Wuhan, negotiated (without worker involvement) a collective agreement which reportedly guaranteed the city’s 450,000 catering workers a monthly wage at least 30 percent higher than the local minimum wage. This top-down, bureaucratic approach was subsequently widely promoted by the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) and this year it published new proposals (2018年餐饮行业工资集体协商指导意见) that it said took into account the rapid growth of internet platforms and delivery services in the catering industry.

However, all wage agreements negotiated by the union so far start from a very low base. For example, the catering industry agreement for Beijing, signed in September this year, which covered 83,000 workers, only gave them a 150 yuan per month pay increase, bringing their guaranteed monthly income to between 2,250 yuan and 2,450 yuan, far below what could be considered a living wage in the Chinese capital.

Moreover, given the often short-term and casual nature of employment in the small private enterprises that dominate the industry in China’s cities, there is no guarantee that employers will abide by these agreements.

Official government statistics from 2017 showed that there were 19.56 million catering and hotel workers in China’s cities employed in the private-sector or self-employed, and another 2.66 million employees in the so-called “urban non-private sector,” which includes government organizations, state-owned enterprises and listed companies.

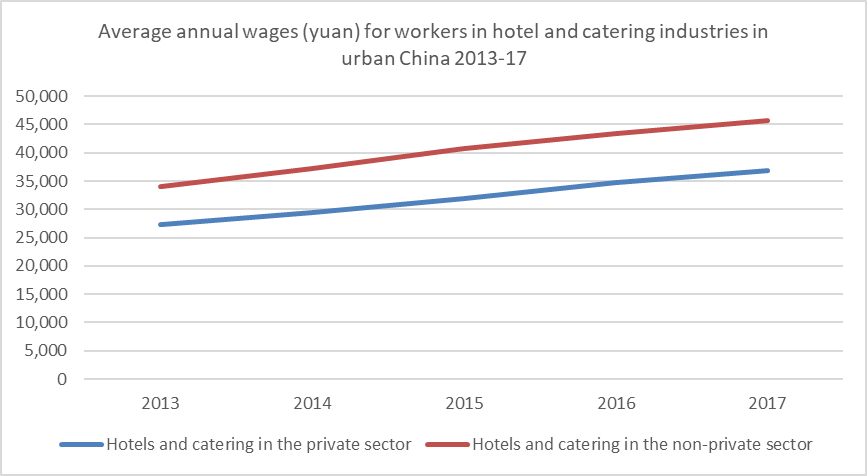

The average wage of hotel and catering workers in the urban private sector was just 36,886 yuan in 2017, while in the urban non-private sector it reached 45,751 yuan, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. See graph below. It is important to note that these average figures include the pay of senior managers and industry executives. The median figure for ordinary workers is almost certainly much lower.

An investigative report on the working conditions of service sector employees in China, published by Worker Empowerment in 2017, showed that many frontline staff employed at hotels in Shenzhen earned not much more than the local minimum wage of around 2,000 yuan per month, while catering workers in Wuhan, pioneer of the ACFTU’s collective agreements, generally earned less than 2,000 yuan a month.

In addition to low pay, hotel and restaurant workers have to endure long hours in an increasingly high-pressure environment. The huge popularity of food-delivery apps, for example, has significantly increased the workload of small restaurants without a commensurate rise in profits. Restaurant owners have even been forced to cut prices to stay competitive, which effectively leaves employees working harder for less pay. However, if restaurants decide to opt out of the online delivery platforms, they risk going out of business altogether. Mr Wang, the owner of a malatang (麻辣烫) restaurant in Shanghai, for example, told Supchina that online takeout orders comprised 80 percent of his business. Referring to the delivery apps he relies on, Mr Wang said: “If you don’t have it, you won’t survive. Everything has moved online.”

In the hotel business, an expose of poor hygiene standards in China’s five-star hotels last year brought attention to the stressful working conditions of low-paid cleaning staff who can only earn a living wage if they clean additional rooms in the same period of time originally allocated, thereby compromising health and safety standards and driving employees to exhaustion. The Worker Empowerment report found that most hotel staff work eight hour shifts but many employees actually work up to 12 hours a day or overnight without proper overtime payments because hotels use a comprehensive working hours system which gives them greater flexibility and lowers costs. Another common cost cutting measure is the widespread use of student interns and agency workers who are often paid less than the minimum wage and have no social insurance.

Just like their colleagues at hotels in the United States, female staff in China have voiced serious concerns about their own safety when faced with harassment from drunk or aggressive guests, but hotel management are usually more concerned with the hotel’s reputation for customer service than the safety of its staff. Yet, these concerns are seemingly never addressed by the trade union.

Rather than focussing on top-down collective wage agreements that only provide hotel and catering staff with the bare minimum they need to survive; China’s trade union officials need to get back to basics and focus on grassroots organizing so that they can better understand the needs of workers and better represent them in negotiations with management. And if management refuses to listen to the reasonable demands of workers, the union in China needs to stand in solidarity with them just as the unions did in the United States.